Mankind has never been a stranger to distraction. Certainly, we live in a time and age in which diversions seem nearly boundless. We turn on Netflix and find show after show catered to our interests. We scroll through social media feeds that have no end, yet this draw to disconnect is no new thing.

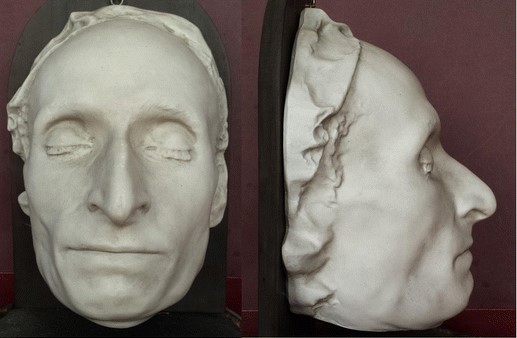

Blaise Pascal, the 17th century French mathematician and theologian, once wrote that “The only thing which consoles us for our miseries is diversion, and yet this is the greatest of our miseries” (Pensées, 171). Pascal in the section of his Pensées (regarding the miseries of life without God) makes the argument that man is drawn to distraction because he would rather not have to reflect upon things such as his mortality, ignorance, and particular sufferings. Man pursues vanity to escape unhappiness. Yet, this escape only escalates his miseries.

Pascal continues, “For it is this [draw to diversion] which principally hinders us from reflecting upon ourselves and which makes us insensibly ruin ourselves. Without this we should be in a state of weariness, and this weariness would spur us to seek a more solid means of escaping from it. But diversion amuses us, and leads us unconsciously to death.” It is this weariness that we all seek to avoid. The weariness of our lives, our relationships, our own inconsistencies, our own failures and longings, our mortality, and yes, our own shame.

The desire to escape is alluring, yet a life patterned by distraction inevitably leads to ruin– And I would argue, not just ruin for one’s self, but also for our respective communities.

Of course, it is distraction which drives us away from contemplation of both God and self. It drives us to shirk integrity and sincerity: to not call sin sin within ourselves but to passively distract ourselves from having to make such self-evaluation. It is the desire unto distraction which would drive us more towards tweeting than prayer, more towards slander than confession, and more towards consuming beauty than delighting in it.

There is a bitterness to life that occurs when the good things here continue to dissatisfy us.

And the effects of this terrifying boredom transmits itself.

It is there in the way we shrink back from a vulnerable yet necessary conversation with a loved one. It is there in the way we blame-shift to avoid dealing with the problems that exist within. It is there in the way we pit our tribes against another in the hopes that we will defeat the source of this weariness.

Pascal mentioned that this collective, human weariness need not destroy us though. This weariness, perhaps akin to that of the Preacher’s efforts in Ecclesiastes, can help us if we were to let it spur us on to something which would ease it rather than towards that which seeks to avoid it.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a medieval monk heavily influenced by Augustine (similarly to Pascal), wrote:

“It is so that these impious ones wander in a circle, longing after something to gratify their yearnings, yet madly rejecting that which alone can bring them to their desired end… They wear themselves out in vain travail, without reaching their blessed consummation, because they delight in creatures, not in the Creator. They want to traverse creation, trying all things one by one, rather than think of coming to Him who is Lord of all. ” (On Loving God, VII).

St. Bernard effectively agrees with Pascal. This weariness causes a longing for something that would cause us to know peace and satiety. Yet, we find this weariness impossible to deal with because its solution is beyond what we can find in other creatures.

When we have a million possible things to do within arm’s reach (or within hand’s grasp of a smart-phone), it is easier to think we can find a permanent distraction to our own weariness than trust that a solution may still be available for us.

It is no secret that both St. Bernard and Pascal saw the Triune God as the solution to such weariness. And of course it is Augustine’s hallmark phrase which they are echoing: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in You.” No amount of distraction, no worldly pursuit or conquest will appease us.

Indeed only life eternal in communion with God can put us to ease and cause us to rest.

And St. Bernard knows what that means for us now who long for that eternal bliss: “To them that long for the presence of the living God, the thought of Him is sweetest itself: but there is no satiety, rather an ever-increasing appetite… Yea, blessed even now are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they, and they only, shall be filled” (On Loving God, IV).

For St. Bernard (and the others), to live now, is to live in anticipation: to not stoop to fulfill an eternal craving with a taste of something that may lead us from that which truly satisfies. Rather, it is to live consciously with the weariness and hunger, to feel our tongues dry for a taste of righteousness, and to acknowledge our own emptiness so that we might be filled by the God who has and will and continues to give himself to us.